The Covid pandemic, 5 years on

Thinking about Covid, five years on.

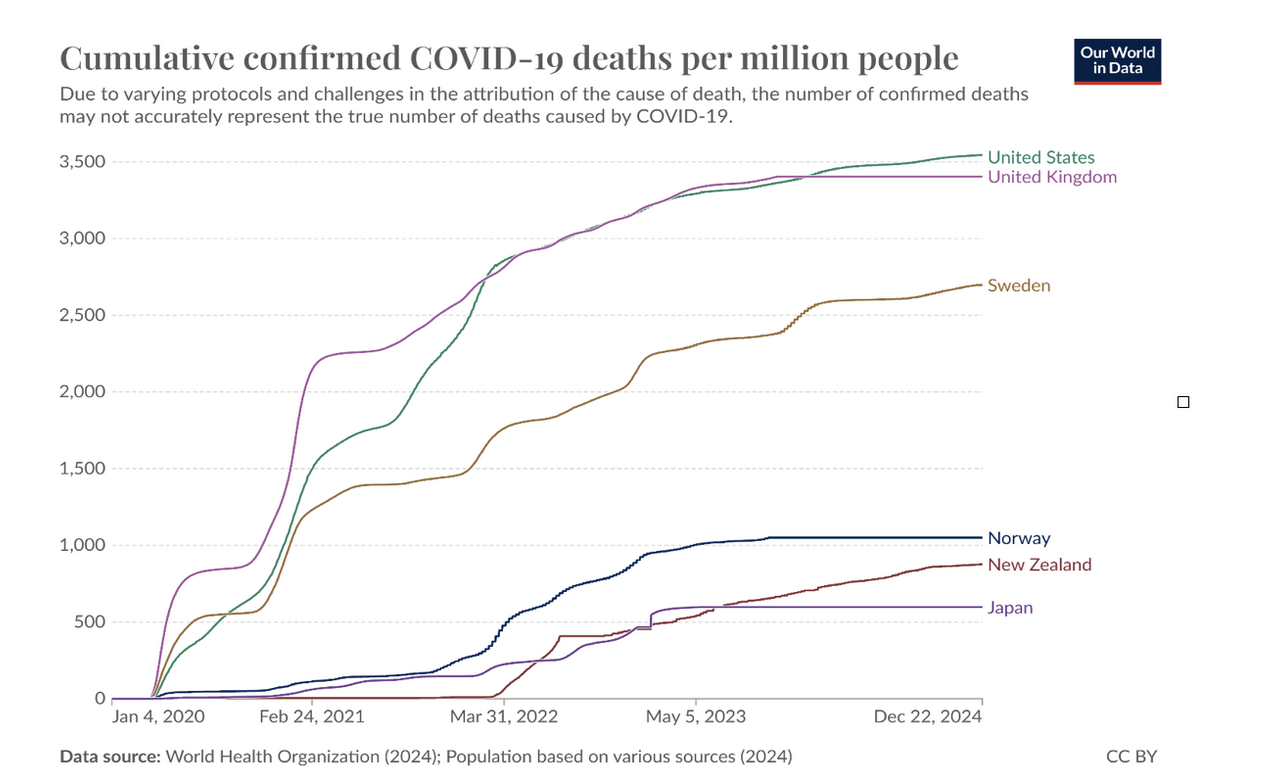

Five years ago, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. For millions, it was literally a defining event of their lives: It killed them. It indisputedly killed at least 7,000,000 people. That’s covid deaths reported to the World Health Organization. The actual number is far higher, and the ongoing impact of the pandemic is also tremendous. Two meaningful parts of that impact are continuing excess mortality, and impact on children, especially how they’re doing educationally. (For example, see Nation’s test scores fall.)

Excess mortality means more people are dying than the historically normal rates. Overall, by SwissRe’s calculation “excess mortality in 2023 was in the range of 3–7% for the US, and 5–8% in the UK.” In 2022 in the US, there were 3.2 million deaths, and so 3% excess mortality means roughly 100,000 people died sooner than they otherwise would have.

Closing schools was clearly a high-impact intervention to save lots of lives. It was backed by a set of models that showed asympotmatic children in close proximity for full days were amongst the largest sources of contagion. (Michael Lewis documents this extensively in his Premonition: A Pandemic Story.) The awful educational outcomes clearly relate to the pandemic, but there’s more happening than “just” school closures. Many students experienced extreme stress or grief, including the hospitalization or loss of loved ones. That was overlaid onto family stresses, and made worse by attacks on teaching students to grapple with the effects of their emotions (“social emotional learning”.) Not grappling with the role of schools in spread means we’re not upgrading school air systems, and we’re going to respond to the next pandemic without a chapter in the playbook.

Politicization of masking, combined with anti-vaccination as a business model have gutted confidence in public health and the confidence of public health officials. I continue to believe that despite mistakes (including digging their heels in over droplets versus aerosol spread), public health officials generally did a good job despite the unknowns of a new disease.

Ignoring the pandemic, pretending it didn’t happen, or pretending that national choices about how to manage it had no impact on deaths leaves us ill-prepared for the next pandemic. That could credibly be measles, bird flu, or even a resurgent covid. Measles shouldn’t be on that list. We have effective vaccines and have had them for years. This bird flu is new, and we ought to be running an operation warp speed to develop vaccines for it. And for a resurgent covid, there’s no reason to expect that all or even a majority of mutations will lead to less transmissible or damaging strains. Mutations are random, as are their effects.

When we threat model, we ask “Did we do a good job?” Part of that is validating the model: does it reflect the system, did we find the expected number of threats? But a lot of it is learning lessons. Stepping back to assess our work. Pretending that the pandemic was not a major part of all of our lives, ignoring the trauma, and ignoring the dramatically different outcomes between countries doesn’t change that. But it does prevent us from doing better today, with the ongoing acute and chronic/long versions of the disease, and with new pandemics waiting in the wings.

The header image is from Sweden’s controversial COVID-19 strategy. I picked it because we have choices that we can make, and we’re making them poorly.