Structures, Engineering and Security

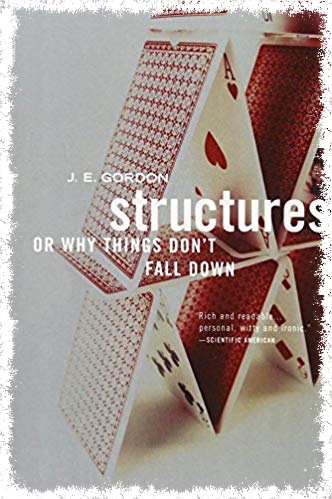

J.E. Gordon’s Structures, or Why Things Don’t Fall Down is a fascinating and accessible book. Why don’t things fall down? It turns out this is a simple question with some very deep answers.

J.E. Gordon's Structures, or Why Things Don't Fall Down is a fascinating and accessible book. Why don't things fall down? It turns out this is a simple question with some very deep answers. Buildings don't fall down because they're engineered from a set of materials to meet the goals of carrying appropriate loads. Those materials have very different properties than the ways you, me, and everything from grass to trees have evolved to keep standing. Some of these structures are rigid, while others, like tires, are flexible.

The meat of the book, that is, the part that animates the structural elements, really starts with Robert Hooke, and an example of a simple suspension structure, a brick hanging by a string. Gordon provides lively and entertaining explanations of what's happening, and progresses fluidly through the reality of distortion, stress and strain. From there he discusses theories of safety including the delightful dualism of factors of safety versus factors of ignorance, and the dangers (both physical and economic) of the approach.

Structures is entertaining, educational and a fine read that is worth your time. But it's not really the subject of this post.

To introduce the real subject, I shall quote:

We cannot get away from the fact that every branch of technology must be concerned, to a greater or lesser extent, with questions of strength and deflection. ...

The 'design' of plants and animals and of the traditional artefacts did not just happen. As a rule, both the shape and the materials of any structure which has evolved over a long period of time in a competitive world represent an optimization with regard to the loads which it has to carry and to the financial and metabolic cost. We should like to achieve this sort of optimization in modern technology; but we are not always very good at it.

The real subject of this post is engineering cybersecurity. If every branch of technology includes cybersecurity, and if one takes the author seriously, then we ought to be concerned with questions of strength and deflection, and to the second quote, we are not very good at it.

We might take some solace from the fact that descriptions of laws of nature took from Hooke, in the 1600s, until today. Or far longer, if we include the troubles that the ancient Greeks had in making roofs that didn't collapse.

But our troubles in describing the forces at work in security, or the nature or measure of the defenses that we seek to employ, are fundamental. If we really wish to optimize defenses, we cannot layer this on that, and hope that our safety factor, or factor of ignorance, will suffice. We need ways to measure stress or strain. How cracks develop and spread. Our technological systems are like ancient Greek roofs — we know that they are fragile, we cannot describe why, and we do not know what to do.

Perhaps it will take us hundreds of years, and software will continue to fail in surprising ways. Perhaps we will learn from our engineering peers and get better at it faster.

The journey to an understanding of structures, or why they do not fall down, is inspiring, instructive, and depressing. Nevertheless, recommended.