Threat Advisory: GPS Attacks [SA-26-01]

Executive Summary

Download the PDFIf your company or organization relies on GPS (Global Positioning System) for location or time information, you should update your threat models in accordance with this advisory’s recommendations about threats to GPS services.

Context and background

Dramatic and sustained growth in GPS attacks (up 500% in 2024) in recent years necessitates re-evaluating existing threat models for applications and services that rely on GPS location-based services. Often seen as presenting a low likelihood of attack outside of military conflict, GPS attacks that disrupt commercial applications, through either spoofing or GPS jamming, are increasingly common and occurring around the world, including the United States.

Almost every major industry could be affected by a GPS attack. Beyond the known and potentially devastating risks to the military and commercial aviation, GPS interference could significantly affect emergency response services, along with the financial, agricultural, energy, shipping, trucking, autonomous-vehicle industries and even consumer applications.

GPS attacks not only pose risks to safety, but also to local and global economies. When GPS attacks cause signal interference that limits or denies access to products or services, those organizations and their markets would suffer financial losses—potentially causing broader, global economic impacts, depending on the duration of the disruption.

With an increase in GPS attacks, a broader geographic scope, and declining hardware costs for these attacks, we are issuing this advisory to explain how the threat landscape is changing and how to apply threat modeling to assess risk to your organization.

Recommendations

Update threat models which reference GPS systems to re-evaluate your exposure to the changing threat landscape. If your organization has a threat modeling procedure, follow it, otherwise use our scenario-specific methodology:

- Determine if your technology or operations depend on GPS for time or location information.

- Consider what can go wrong if GPS were to become unavailable or inaccurate.

- Consider mitigative or responsive steps.

The analysis can be done in an hour or less if your GPS systems are lightly or not impacted. If you are impacted, understanding how can take up to a few hours per business line, and deciding what to do can be complex and take longer.

Scenario-specific threat analysis methodology

We organize threat modeling work according to the Four Question Framework. Those questions are:

- What are we working on?

- What can go wrong?

- What are we going to do about it?

- Did we do a good job?

This Advisory explains how to approach the first three questions in the scenario-specific context of rising GPS attacks.

Determine if your technology or operations depend on GPS for time or location information. (“What are we working on?”)

Organizations with legacy systems that pre-date their threat modeling should create scenario specific models which they’ll use in the next step to help identify security gaps.

Threat modeling for GPS issues does not require detailed or high-fidelity system diagrams. Quick sketches that show the major components of a system and how they relate are sufficient. These will often be 4-8 components and lines connecting them.

Consider what can go wrong if GPS were to become unavailable or inaccurate. (“What can go wrong?”)

Perform analysis of worst-case scenarios in this phase. Defer consideration of likelihood until after this step. If you have multiple product lines that might be impacted by GPS attacks, you can either have the same team do the work sequentially or ask product owners to do it and report back. This applies to user-accessible GPS navigation, GPS trackers, and other such systems.

Time

While GPS is best known for providing location data, calculating that location data requires incredibly accurate time information, and so many systems, from your phone to large data centers, will often use GPS to determine what time it is. This paper uses time to refer to the “wall clock time.”

You should look for threats of GPS spoofing and jamming attacks (denial of service) to both time and location. (The word “threat” is used to mean a potential future problem; it is not shorthand for “threat actor.”)

Organizations with structured threat modeling programs should search for the terms “GPS,” “navigation,” and “location” in their existing Threat Model documentation. Location will probably return a superset of the relevant results.

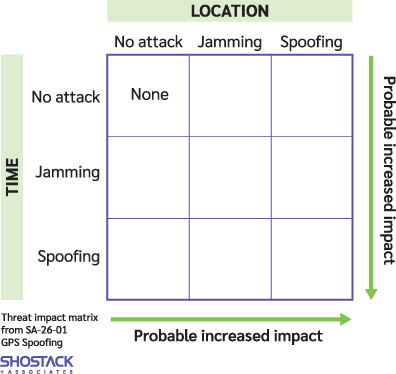

Organizations without structured threat modeling programs should assess the impacts of both spoofing and/or GPS jamming (often called interference or denial of service attacks). A matrix such as the one shown in Figure 1 can be used to consider impacts, asking if each of location or time are unaffected, jammed or spoofed.

With or without a structured threat modeling program, this effort will frequently benefit from the perspective of front-line staff, who may have experienced hardware failure, “urban canyons,” or other failure modes.

It may be helpful to consider the duration of spoofing, with categories of transient (up to an hour or a day) or sustained (at the extreme end, attacks in the Middle East and around Ukraine have persisted for over a year). Aside from the military and political impact to areas of conflict, tools and applications that rely on GPS for everyday consumer use such as dating websites, product placement, banking, or transportation and delivery services may be impacted. Focus on worst case impacts, and consider likelihood as part of mitigation selection, rather than while assessing what can go wrong.

For example, the top middle box would contain the impact of “location is jammed, but time is unaffected.”

Consider mitigative or responsive steps. (“What are we going to do about it?”)

The form of defense will depend on where you stand in the supply chain. End users of technology (say, trucking companies) will have fewer options than those who create it. Those delivering high-end technology (for aviation or maritime) or primarily urban systems will have more options.

How to Mitigate GPS Attacks

Mitigation options differ by:

- Role in the technology ecosystem (technology producers versus systems operators).

- Sector.

- Geographic area of operation.

Those building (technology producers) should assess their dependency on GPS for location or time information and consider technology improvements and customer communication. Decision factors will include cost of improvements, improvement timelines, likelihood and impact. The process to design, build, and deliver appropriate resilience may take multiple years; these organizations will need to help customers understand roadmaps, contingency options, and costs.

Systems operators and technology producers who depend on GPS will have more constrained choices, and will need contingency plans, to understand their vendors’ plans, and how those plans relate to their depreciation and refresh cycles. For many, detective capability and creating plans for when upgrades will happen will be an appropriate response.

Technical mitigations could include:

- Updating or replacing GPS equipment. This will be complex and expensive.

- Adding additional sources of location or time information, including alternate satellite systems, cellular location information, or wifi-derived location.

- Improving software to be resilient if location or time information becomes unavailable or unreliable.

The OPSGroup report contains quite deep aviation-sector specific mitigation recommendations. The Stanford GPS lab has a wide set of academic publications which will be useful to technology creators including titles such as: Real-World Spoofing Detection and Characterization Using Low-Cost Receivers, or Protection Levels Against Spoofing Using Dual Antennas: a Practical Approach.

The Evidence Behind This Advisory

In 2024 OPSGroup reported: “This year, a 500% increase in spoofing has been observed. On average 1500 flights per day are now spoofed, versus 300 in Q1/Q2 of 2024.” (The OPSGroup, GPS Spoofing Final Report, September 6, 2024.) This spoofing was centered in the Middle East, including Cyprus and Lebanon.

- In December 2025, the New York Times reported: “At least one in five flights in the Caribbean has experienced problems with GPS navigation since early September, according to data provided by Stanford’s GPS Lab.” (Riley Mellen and Anatoly Kurmanaev, U.S. and Venezuela Jam Caribbean GPS Signals to Thwart Attacks, Raising Flight Hazard, New York Times, Dec 20, 2025)

The most common type of GPS interference is created by devices called GPS jammers, which essentially broadcast noise that drowns out the signal and makes it difficult to calculate position and time.

The jammers range from hand-held devices to complex systems located on aircraft and warships. Their sophistication and availability have increased drastically since the start of the war in Ukraine, where both sides extensively interfere with satellite signals to defend themselves against drones and missiles.

The International Maritime Organization, International Telecommunication Union and the International Civil Aviation organization issued a joint statement on the problem.

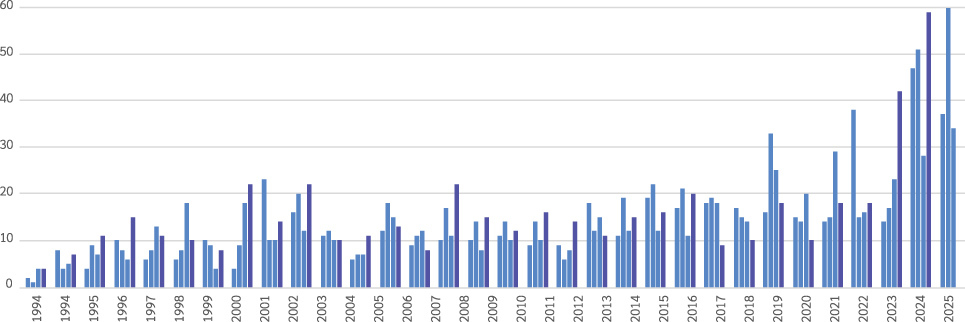

Shostack + Associates analysis of Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS)* data shows a sustained increase in reports of GPS issues starting in late 2023 (Figure 2). ASRS data is mostly, but not entirely, about US flights and American operators. ASRS is operated by NASA as part of their “Aeronautics” mission.

Evidence assessment

Shostack + Associates has assessed the quality of evidence for location spoofing and GPS jamming and find it compelling. The OPSGgroup report presents extensive reasoned analysis and recommendations. The New York Times report uses data from a Stanford lab as well as other labs corroborating the evidence. The joint statement from three major international organizations is limited in specifics, but corroboratory. We consider our ASRS analysis as further corroborating evidence that the problem is emergent and ongoing.

The ASRS dataset represents a set of voluntary safety reports made by flight personnel. Reporting is not mandatory, however, the increase in reports of GPS issues is clear.

We are hesitant to even relay phrases like ‘dramatic growth’, but in this case, the sources have credible, multiple source, ongoing monitoring that make it unlikely that earlier attacks went unnoticed.

Closing

Shostack + Associates is frequently asked “how often should I review or update my threat models?” Our answer is:

- When the threat landscape changes. This is rare.

- When your technology changes substantially, such as adding new components, new technology stacks, or new boundaries.

- At least annually, depending on your rate of technical change.

The increase in credible reports of GPS spoofing, combined with geographic spread and the decreasing cost of hardware for the attack indicate a change in the threat landscape that would trigger updating threat models.

FAQ

Why are you issuing this advisory now?

Shostack + Associates has been noting reports of GPS issues for several years, including them in our Appsec Roundups for May 2024 and August 2024. The attacks are sustained and geographically diverse. We are concerned that:

- Militaries may have gone from considering GPS attacks disproportionately impacting on civilians to seeing them as an accepted and normal part of conflict.

- The tools for GPS attacks are falling in price while increasing in quality, which enables broader adoption by non-nation state attackers.

- The geographic spread covers many regions, including major shipping areas such as the Strait of Hormuz and the South China sea, as well as areas of military conflict.

Who should be involved in the analysis?

The analysis should be sponsored by a senior leader in the organization who can drive a mitigation project if one is needed. A CTO, VP Engineering, CIO or VP of Operations may be an appropriate leader. Larger organizations will delegate as appropriate, probably to product line owners.

How should we do the analysis?

The key activity is meeting to understand products and impacts of GPS spoofing. This should take up to an hour per product. Organizations with Product Security Incident Response Teams (PSIRTs) should leverage them.

What records should we create?

You should record that you performed an analysis, the actions you took, and the reasons for them. (We are fond of “Architectural Decision Records,” a widely adopted format.) Some version of the record should be made customer-ready, especially if you sell GPS-enabled technology. Even if you take no action, the analysis can be good evidence of diligence in case of future problems.

Can my threat modeling tooling help?

Yes, for example, Threat Modeler and Irius Risk have issued a blog post with both commentary and how to.

Isn’t this just a problem in conflict zones?

No. While the most prominent examples are currently coming from conflict zones, the tools that are being built could be deployed anywhere. The NASA near miss data from ASRS shows a rise in US incidents, and should be taken as a warning.

Why do you think GPS affects my organization?

You know your organization better than we do. We’re advising you to update your analysis.

Where can I learn more about the Four Question framework?

We have a whitepaper on the topic, the Threat Modeling Manifesto is structured around it, and the definitive work on threat modeling, Threat Modeling: Designing for Security is structured around it.

What about other outages?

On January 4, 2026, Greek air traffic control radio was disrupted for several hours. The cause has not been determined, and we are treating it as a coincidence, worth mentioning only to say we don’t currently believe it was GPS-related. This advisory is focused on high-credibility evidence of GPS attacks.

Revision History

- SA-26-01, version 1.0 published January 22, 2026. Download as a PDF

- Version 1.01 - Updated Jan 22, 2026 to include Threat Modeler/Irius Risk blog post.

Footnote

* The Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) was established in 1976 as a partnership between NASA and the FAA. ASRS is confidential, non-punitive and is available to all participants in the NAS who wish to voluntarily report safety incidents and situations.

The fine print

This advisory is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-4.0 license. Additionally, if you operate a service of collecting and distributing security advisories to your customers, you may copy and distribute this advisory as part of that as service as long as you include a prominent link to the original and do not alter or remove attribution.