Apollo 15 Lunar Rover Vehicle

What can a signed Apollo 15 print teach us about modern threat modeling and risk management?

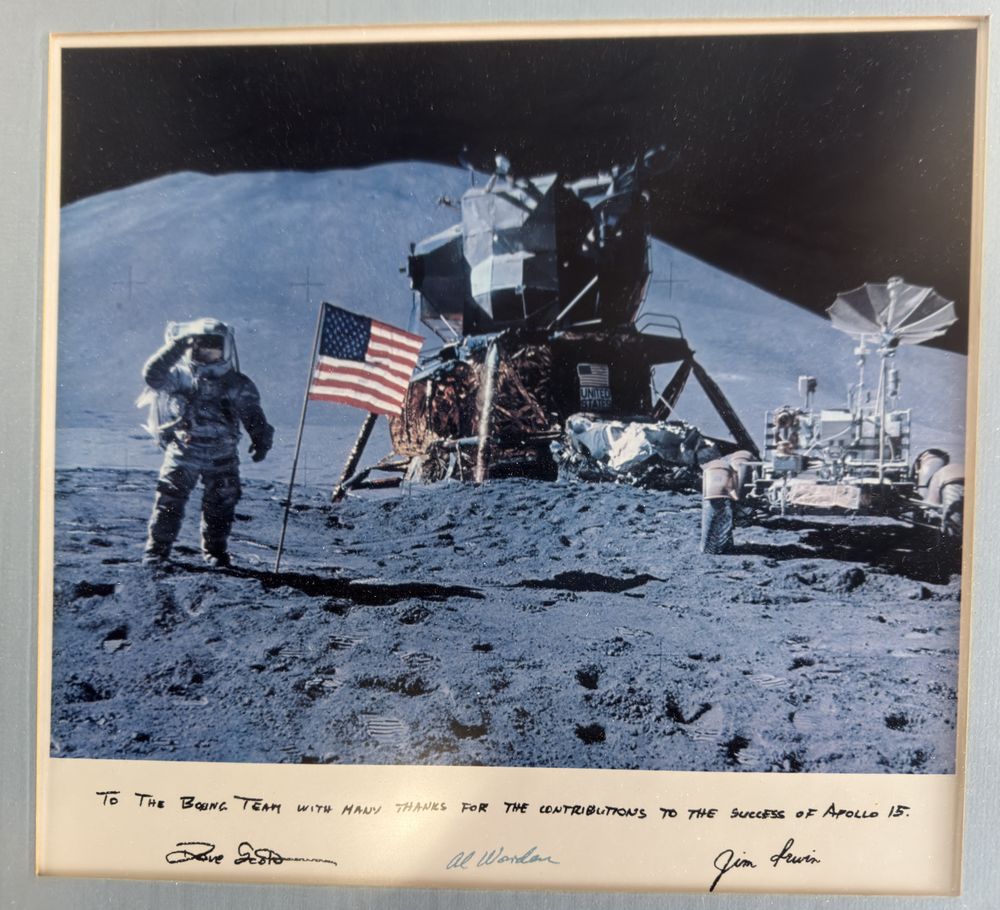

I was thrilled to find this photo at a thrift store. There’s a typewritten letter on the back from Earl Houtz, LRV program manager, which is .. not exceptionally personal, leading me to think this could have been one of several sent to the LRV team. I imagine it hung on a wall at Boeing, went home with someone during a re-org and ended up at a thrift shop. I want to reflect a little on what the photo shows us about high-risk technology development.

The Photograph

Before I get there, let me talk about the photograph. I was able to track down exactly when it was taken because the Apollo missions are well documented with audio transcripts and photograph collections. I first thought that it was a colorized version of AS15-92-12446 but Jim Irwin is a little far from the flagpole for that to be a match. (See the EVA 2 transcript.) I’m now confident that it’s a print of as15-88-11866 because it’s a wider field than as15-88-11865. The Flickr version has a nice description, but less color intensity than the NASA.gov version, which is surprising because the Flickr version is from NASA’s Johnson Space Center. A comment in NASA’s Lunar Surface Journal says “Few Apollo photographs have been reproduced more often than this color photo of Jim, the flag, the Rover, and the LM, with Mt. Hadley Delta in the background. Note the bright, rectangular pattern on the high-gain antenna. The pattern is produced by sunlight reflected by the mirrored tiles on the top of the TV camera. A detail shows that Jim has a strap-on pocket on each thigh.”

It’s interesting that film was so precious that the film magazine takes us all the way from the start of EVA-3 to the start of the trip back to Earth — you can see the moon shrinking as the frames progress.

The inscription

Having contextualized the picture, I want to talk about the inscription at the bottom. It reads: “To the Boeing Team with many thanks for the contributions to the success of Apollo 15.”

The Apollo program employed over 400,000 Americans across the country, including workers at Boeing who made the Lunar Rover and Playtex in Massachusetts, who hand-sewed the iconic spacesuits. Many of the astronauts made a point of visiting local manufacturers wherever they traveled to encourage them to recognize the dangers and make sure what they made was ... higher quality than was typical from low-bid government contractors.

The human end of managing and aligning 400,000 people means that, as many technical challenges existed, many of the challenges weren’t technical. In Project Apollo: The Tough Decisions, NASA assistant administrator Robert Seamans presents what he saw as the tough decisions in the program. They were about how to structure centers, the complexity of dealing with contractors, and the like. These sorts of decisions have a great deal in common with decisions companies need to make today about how they’ll deliver. Roughly the only technical decision that Seamans recounts was the deeply technical single vehicle/multi-vehicle debate. Seamans credits von Braun for agreeing that his single vehicle approach was less likely to succeed and ending the debate.

I see this picture and the autographs as parts of that process. Thanking the Boeing team for making the mission successful is something they could tell their kids about. Hanging it on an office wall tells people that what they do here is important. Find it also tells a story about Boeing: Someone let this go when they cleaned out an office.

Risk

One of the themes I’ve been exploring recently is that risk measurement is dependent on iterations. That’s both part of how we might talk about it (“one in ten”) and that we can test if our predictions are correct. If we then have roughly ten instances and the thing happened in one of them, we had a good prediction. If it happened in six or seven, we learn that our risk assessment was not very precise. For more on this, see my risk is not a hammer talk at Usenix.

Apollo pushed the bounds of what was possible, and involved a lot of very expensively checking on future dangers. Could a spacecraft navigate to the moon and back? Were there unforeseen dangers in trying to dock in lunar orbit? Could the computer function as a useful pilot assistant? David Mindell covers the fascinating technical and human challenges of creating and using that function in Digital Apollo.

Breaking down the new hazards into multiple missions was referred to as “buying down risk.” The decisions about which hazards to bundle was a matter of balancing the danger with the goal of beating the Russians and Kennedy’s deadline (“by the end of this decade.”) There was no reasonable or satisfying way to quantify the dangers involved. So they settled for “it worked once.” And in fact, each time something was shown to be feasible was a reduction in risk, even if that reduction was impossible to quantify.

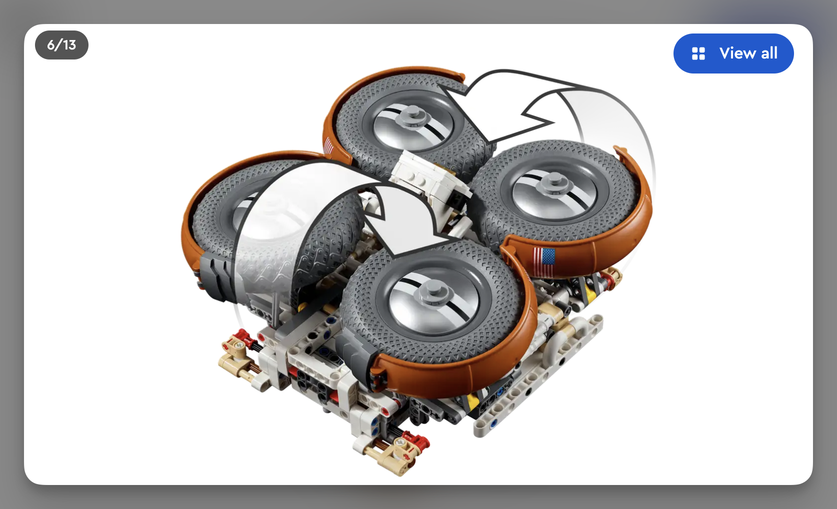

Back to the real thing, and risk: The LRV was an example of adding hazards. It added both weight and mechanical complexity, and if it had failed, the astronauts might well have been stranded with limited oxygen far from the lander. The mechanical complexity is well-reflected in the Lego model. The Lego wheels fold up to a flight configuration, and that model was very complicated to build, even though it doesn’t account for the electrical cabling. I do want to mention, I learned a lot about the rovers by building the incredibly fun LEGO Apollo LRV (42182). The LRV may be my second favorite NASA Lego kit, after the Saturn V.

As in any good risk calculation, there was also a reward: The astronauts could go further, get to sites that wouldn’t have been accessible on foot, and carry more tools with them and rocks back.

Most of the good histories of the Apollo program blend the technical, economic and managerial aspects into one story. And those factors are in any interesting technology project. Motivating people to deliver and recognizing them when they’ve done it... well, it motivates me more than fifty years later.

Disclaimer: Lego and book links are affiliate links, I make money if you click on them or order stuff.